This is definitely a TL;DR article but incredibly important for our industry. Please pardon the lengthy piece but it required a thorough explanation. If you want to skip all the operational and regulatory mumbo jumbo and to the juicy part of the article, skip to - The Insidious Nature of Marketplaces.

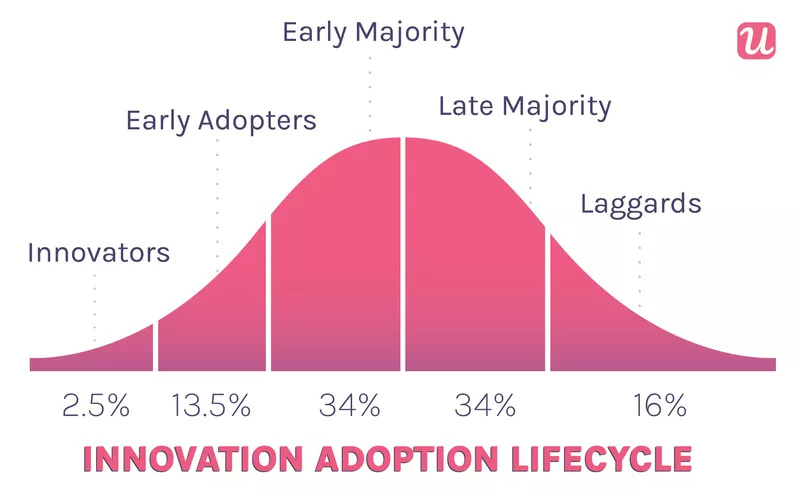

The wine industry both suffers and benefits from our latent use of technology. By being late to the game, we sometimes miss tremendous first-mover advantages. Sometimes, the choice of missing the bandwagon is forced upon us due to stringent alc-bev regulations (TikTok - get us an age gate!!!). Other times, we're lucky to be late and avoid shiny objects that drain time and money - Clubhouse, NFTs, Blockchain, Pinterest, etc. Periodically, we are fortunate to be in the late majority of the adoption curve, so the learnings from other industries can be successfully applied to ours.

MARKETPLACES

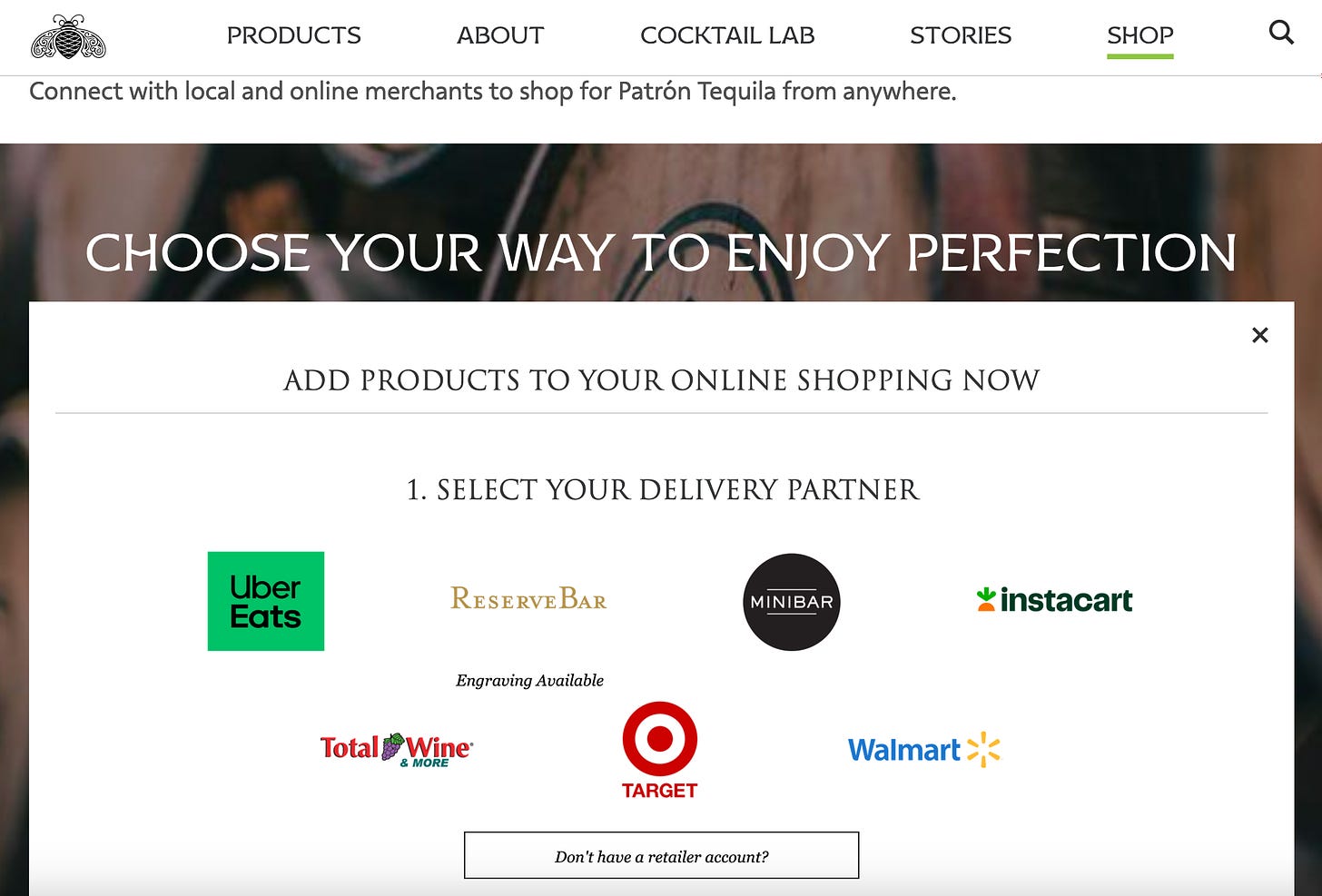

One of those trends is marketplaces. On their face, marketplaces seem like good propositions. Their job is to represent products on a giant digital shelf to help consumers choose from the broadest selection possible and be able to purchase from a single shopping cart. They are responsible for marketing, customer acquisition, and customer service.

Marketplaces will inevitably emerge in mature online categories. Frankly, they are one of the favorite VC models (the other being platforms with giant growth of Monthly Active Users - MAUs) and are driven as much by industry and consumer needs as investor financial support. Marketplaces usually earn their money by either earning a small part of the transaction or, especially, through disintermediating other sales tiers. That makes the wine industry particularly inviting with the ability to potentially disintermediate two tiers - wholesalers AND retailers. Or even more compelling, to disintermediate three tiers for imported wines. They generally either ship the products from a centralized warehouse or have the seller drop-ship them, or sometimes both (Amazon), and earn their commission from the sellers in the process.

But with wine, marketplaces are mired with challenges that don't exist in other categories. You’ll have to bear with me as I open the casing and share how the sausage is made. It might be a bit detailed and insider baseball, but it’s important to understand this model.

The Regulatory & Operational Challenges With Marketplaces

First and foremost, selling wine via consignment is illegal. This restriction is a remnant of the 21st Amendment to ensure the industry's three tiers are distinctly separate and that they cannot exert pressure or influence on the other tiers.

From Dickenson Peatman & Fogarty, "Tied-house laws are federal and state laws that attempt to prohibit brewers, distillers, winegrowers, and other alcohol beverage suppliers from exerting undue influence over retailers. In theory, such laws minimize the potential for unfair business practices in the industry and protect against social ills such as over-consumption."

For example, if Wine.com were providing marketplace "consignment services” in conjunction with their retail activities, that would be a risky endeavor because it blatantly defies the tied house laws. However, retailers, wholesalers, and importers often try to skirt this concept through “extended terms,” which technically don’t hold up for regulators but often mirror actual business realities.

Because marketplaces are unlicensed entities, they need alternative ways to be able to sell the wine without acting as a retailer. To facilitate the mechanics of this, they operate as the "buyer's agent" or "seller's agent" and, in some cases, serve as both. Essentially, the site acts as an "agent" on behalf of the consumer to communicate the order of wine (s) to the seller. They then earn a fee from the buyer on behalf of that service. Providing these types of services requires convoluted financial mechanics behind the scenes*.

Also, there are laws on how much a marketing agent can "avail" itself of the transaction. Regulators frown upon percentages of the transaction, which is ironic and ridiculous because every credit card company has been doing so since the dawn of that form of payment, and they never balk at those transaction fees. As such, many agents create strange pricing models, such as giant tables of flat pricing that equate to percentages, tiered pricing models, subscription plus transaction surcharges, and many other complicated pricing models. However, even with these models, they generally want to see the total amount taken from the agent to be at most a 10% amount. Some platforms simultaneously operate as a "Seller's Agent" representing the retailer/winery to "facilitate an order on behalf of the seller." For this service, they can earn another 10%. However, 20% is lean margins to support platform development, staff, and customer acquisition costs. Some marketplaces charge more but are likely on very tenuous grounds for many state regulators and would fail if they were audited.

Are you still awake? Let’s grind through the rest of the regulatory hurdles.

Even overcoming the revenue earnings, being a marketplace comes with some fundamental, challenging regulatory restrictions -

"Principle 1: Only licensees may engage in activities that require an alcoholic beverage license."

This refers to selling alc-bev, which means that a marketplace website is technically not selling; it is just a marketing site that collects customers and funds. That means they should be distinctive about telling the consumer which retailer(s) they are buying from.

"Principle 2: Licensees are ultimately responsible for the actions of third parties hired to conduct any activities involving the sale or marketing of alcohol on their behalf."

This is where the rubber meets the road. At the end of the day, the winery or retailer's license is at stake. So if they over-ship to a consumer, send adult beverages to an underage drinker, etc., the licensee will be at risk. Moreover, to facilitate these transactions, they either leverage the seller's license (which may have state and volume restrictions) or pass the transaction through a web of "clearing licenses."

"Principle 3: The flow of funds must be controlled by the licensee and third parties should not share in the profits, but may receive service fees. From the ABC's 2011 advisory: "the Third Party Provider cannot independently collect the funds, retain its fee, and pass the balance on to the licensee."

*This is the sticky wicket that drives marketplaces crazy: a wacky electronic flow of funds often leads to an escrow account or an instant distribution across all the participating entities (which becomes more complex with more sellers in the transaction). While technology can solve this, it adds unnecessary complexity to building the system and managing the financials. I doubt that many regulators have audited the financial flow of most marketplaces, and if they did, they'd find them far out of compliance.

"Principle 4: Unlicensed third parties cannot take title to alcoholic beverages. The licensee must retain control over the storage and fulfillment of alcohol to consumers."

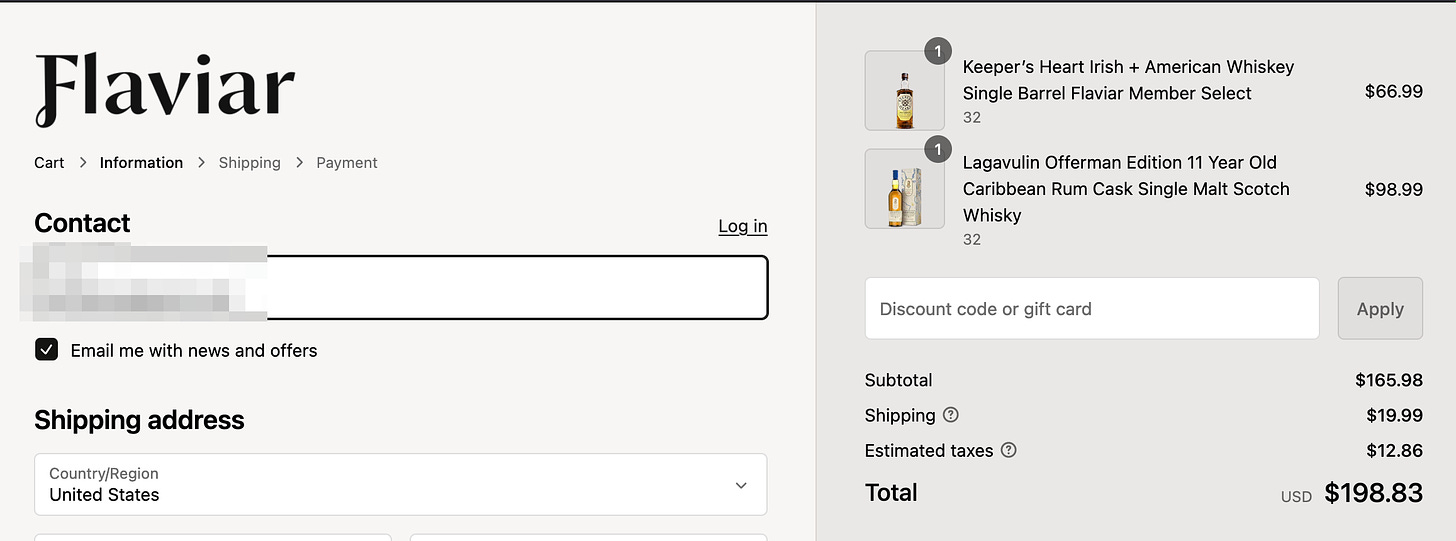

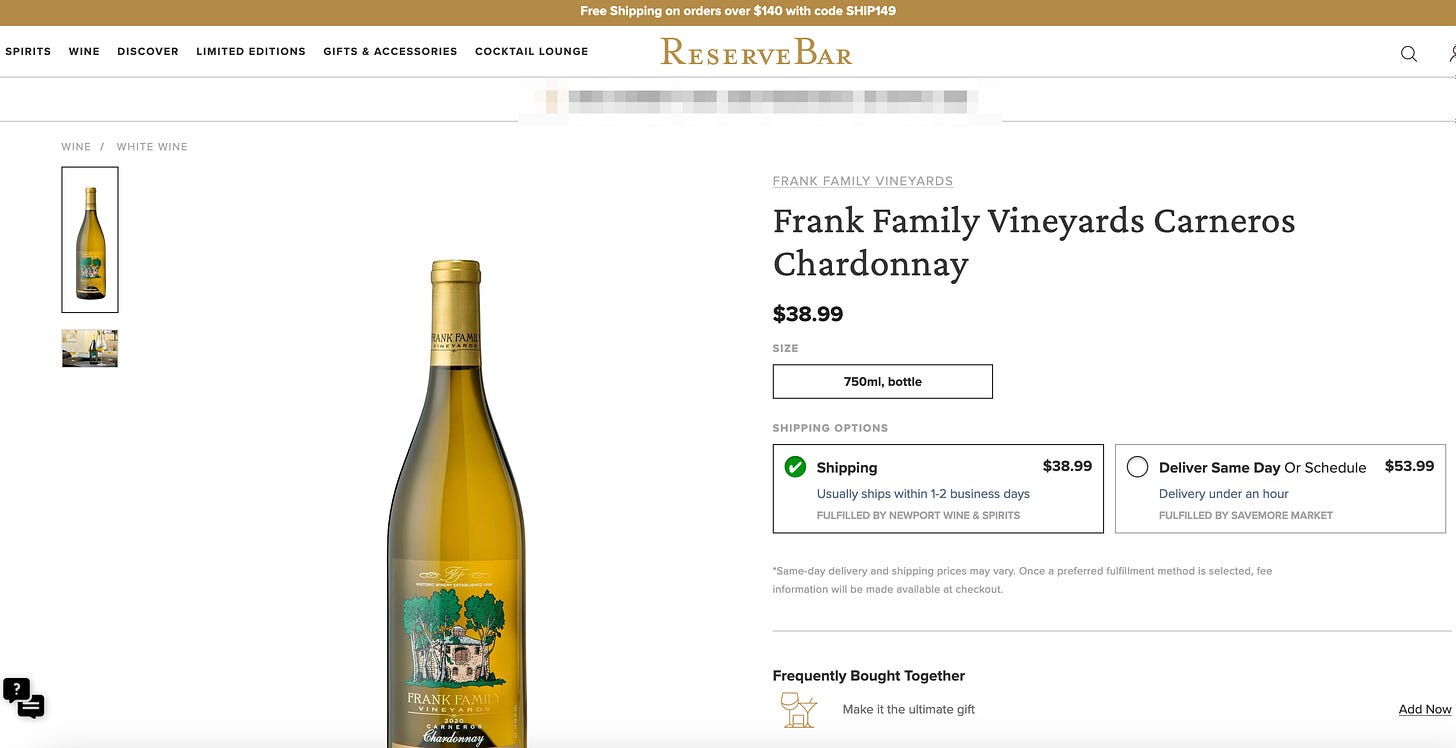

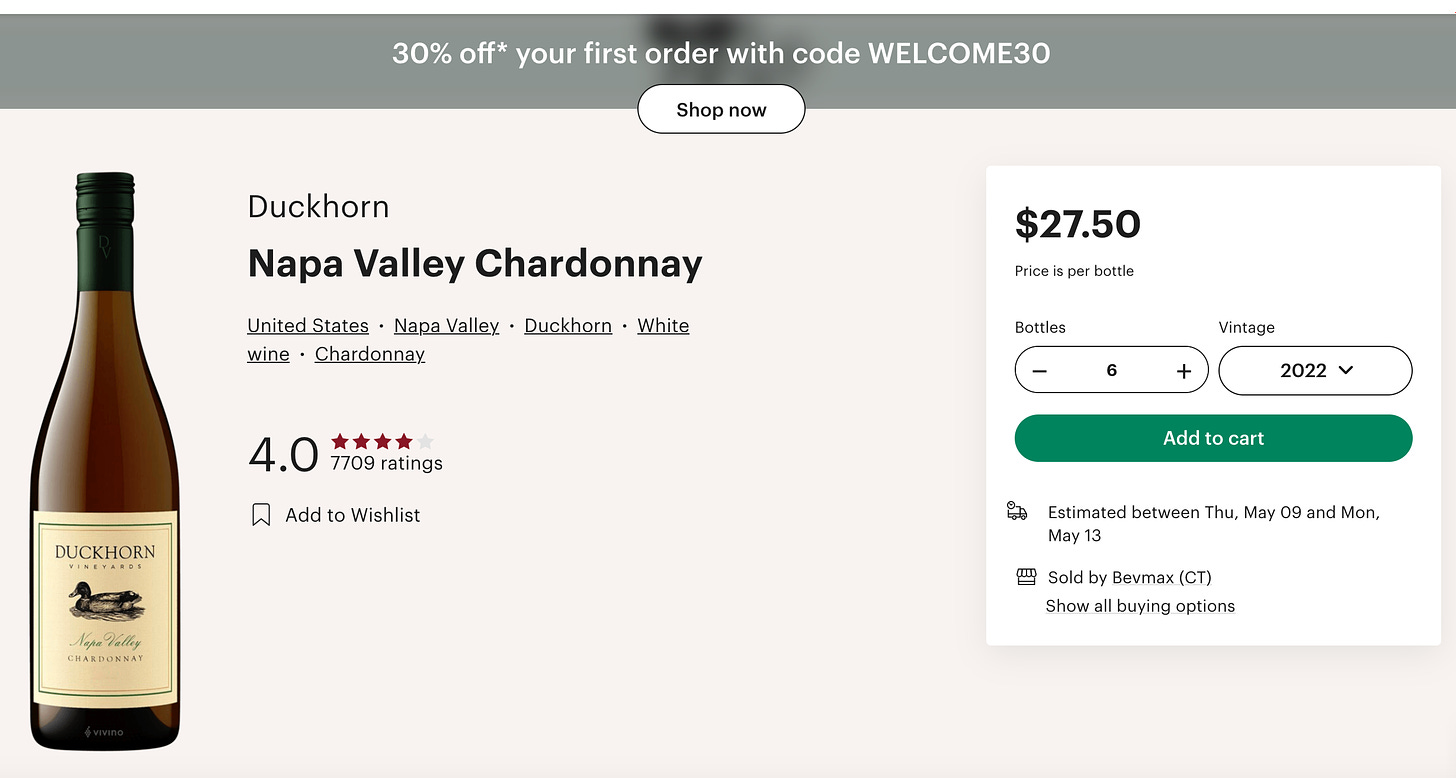

This also creates a litany of challenges because the licensed warehouse has to be where the winery creates a second inventory location at a centralized 3PL like WineShipping. Unfortunately, no 3PL shipper has earned the business of the majority of the industry. Still, sadly, it's often unprofitable for them or the winery if they are not shipping enough DTC or have too many slow-moving SKUs. The alternative is to have them drop ship it from their winery or shipping partner, which creates other challenges around cost. The first bottle of wine is an expensive lift, so single or small orders from multiple retailers are cost-prohibitive. If the cost is $9 for the first bottle, who will absorb that cost if the consumer buys three bottles from three wine sellers (essentially adding $27 total cost to shipping or $9 per seller)? The winery? The retailer? The consumer? From the marketing agent's 20%? What if it's two bottles? The floor for the price of the wine to substantiate subsidizing shipping differs per seller (retailer vs winery). Still, the economics only make sense if the bottle exceeds a significant SRP per bottle or a larger basket from each seller (generally six bottles+).

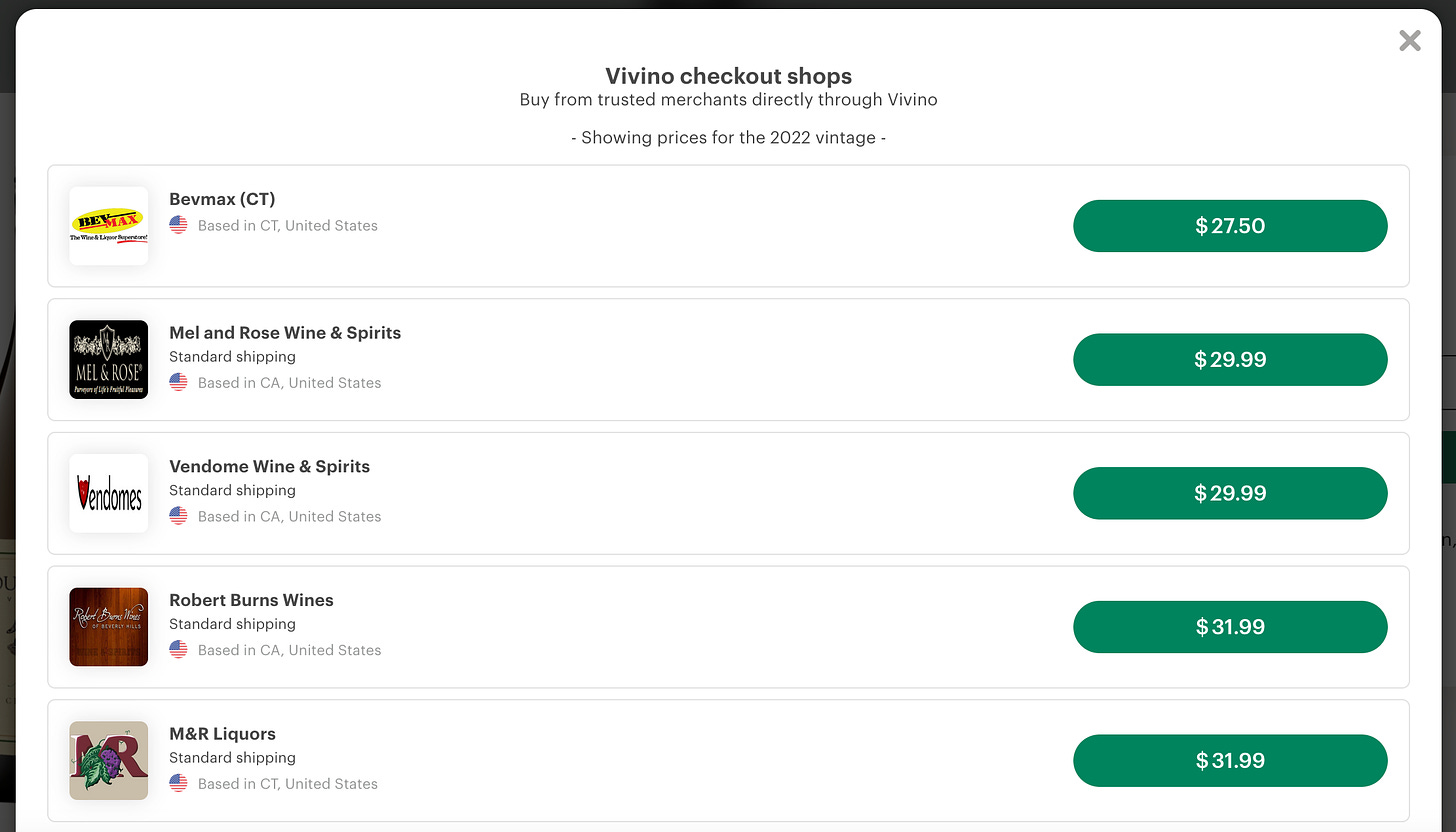

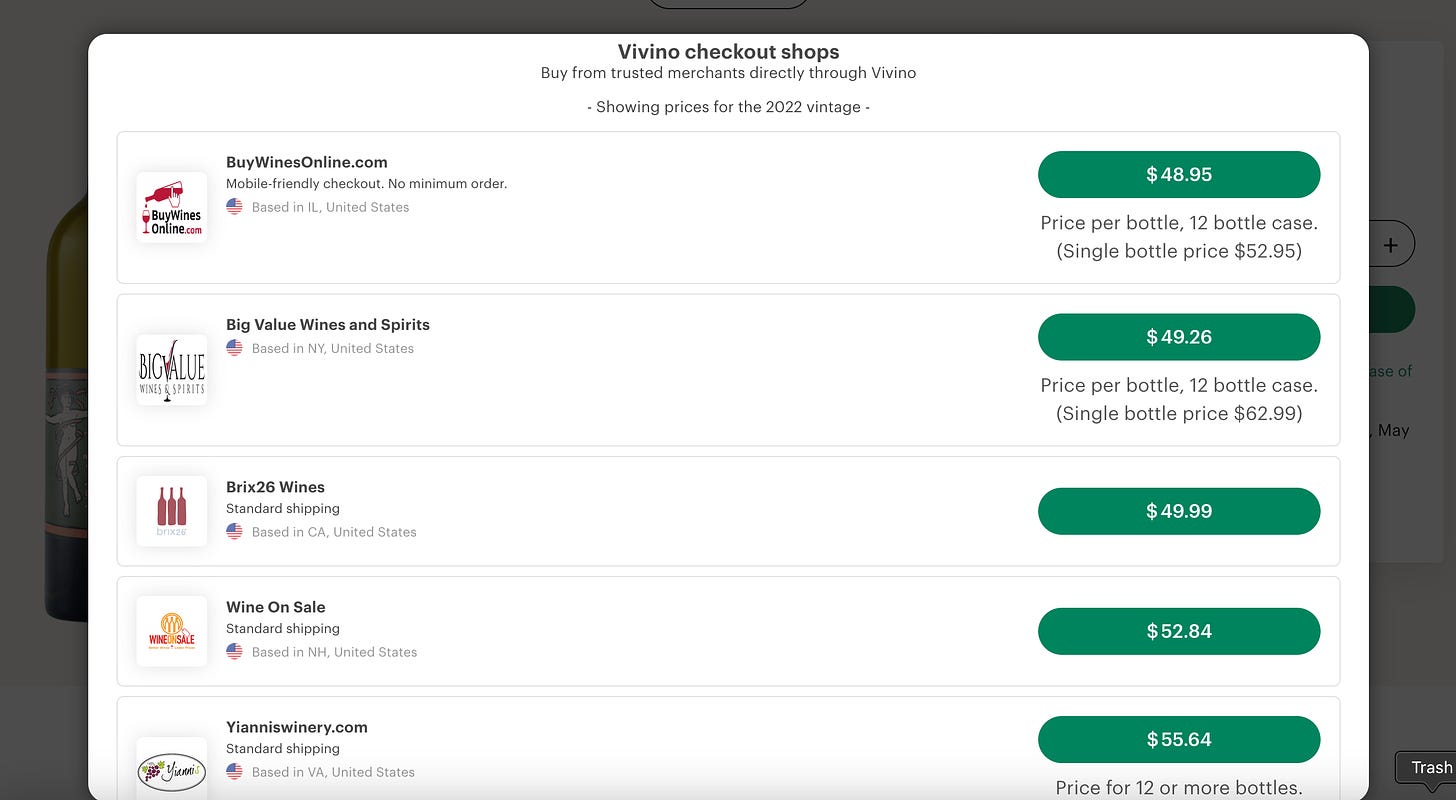

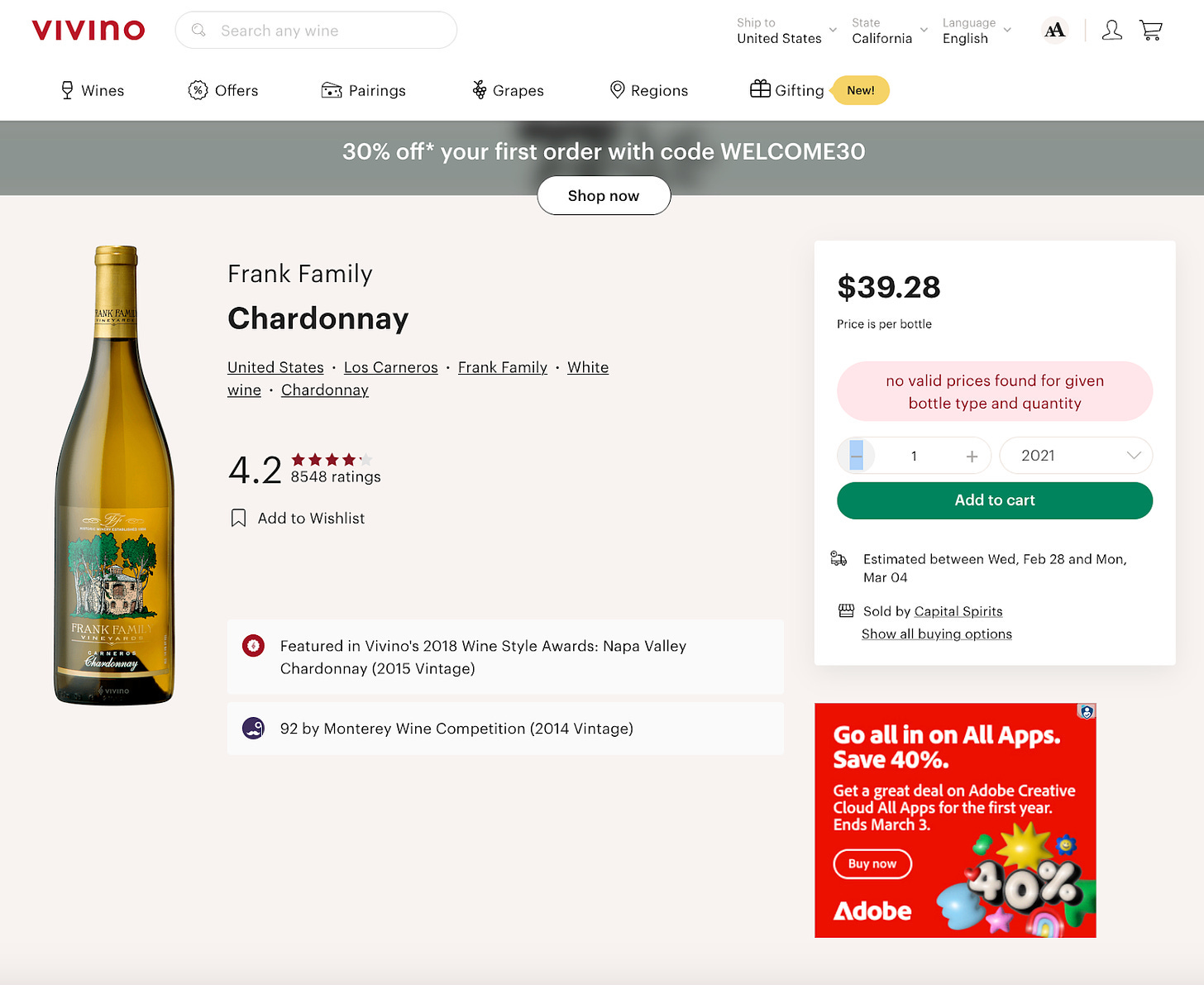

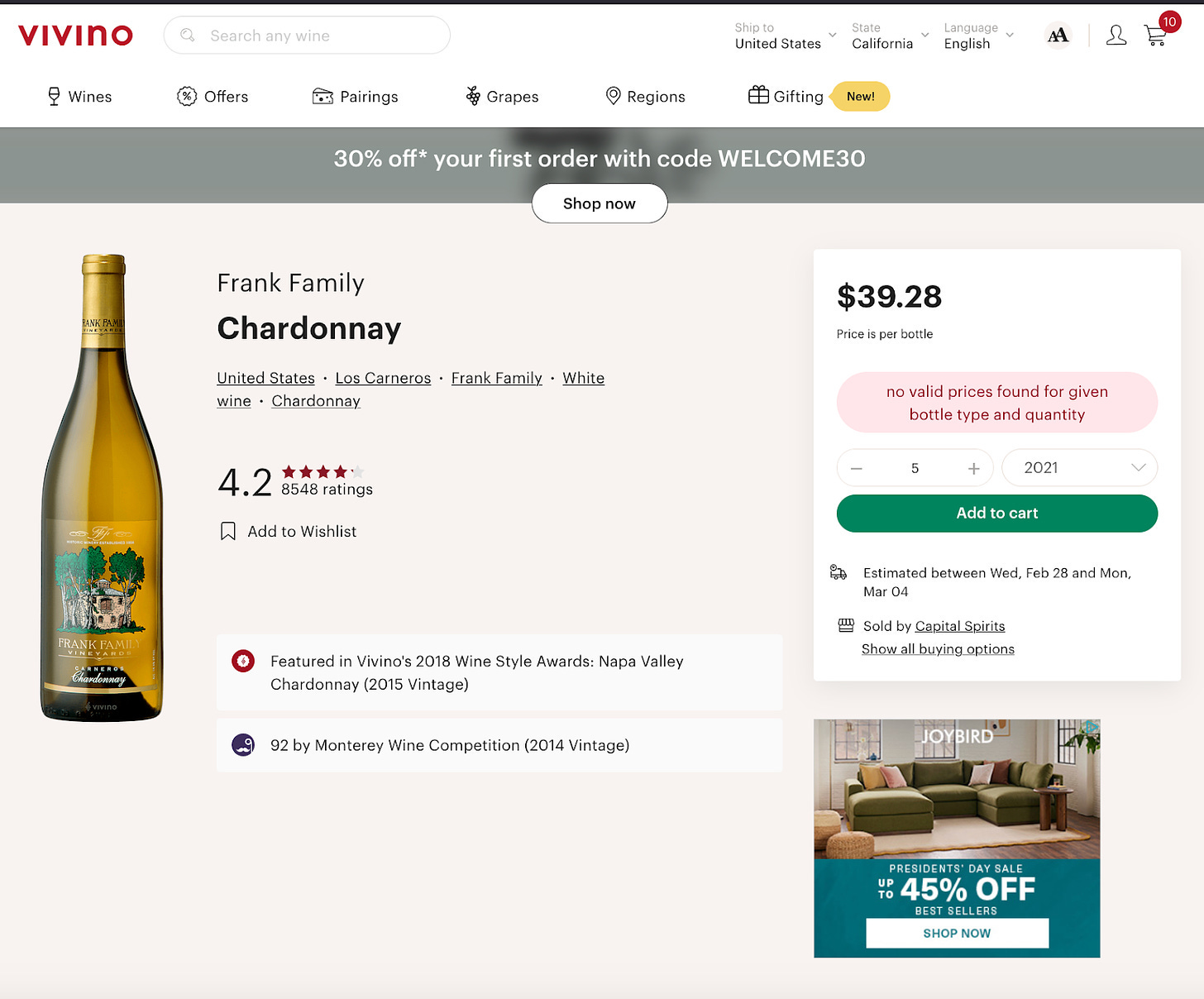

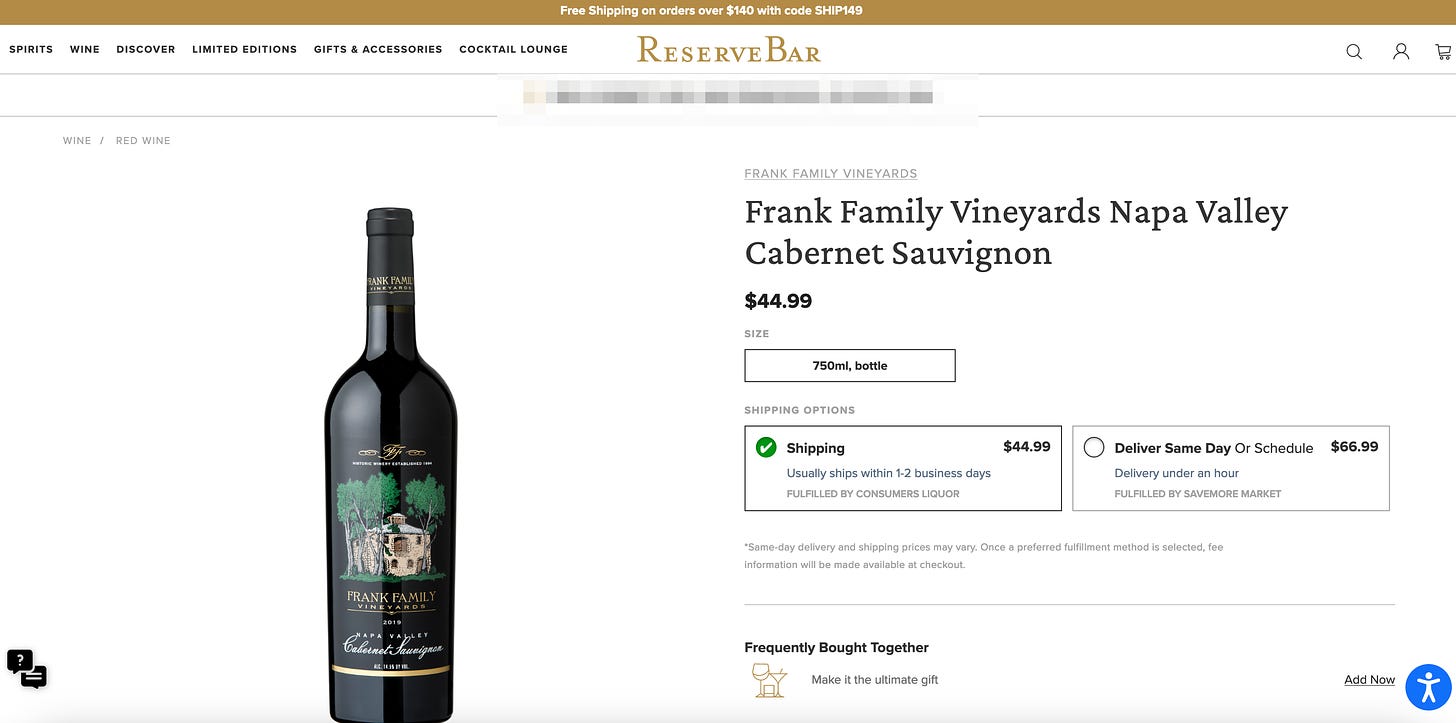

As you can see with the Vivino marketplace, no retailer will absorb the marketing agent fees and shipping for less than 6 bottles at a premium price.

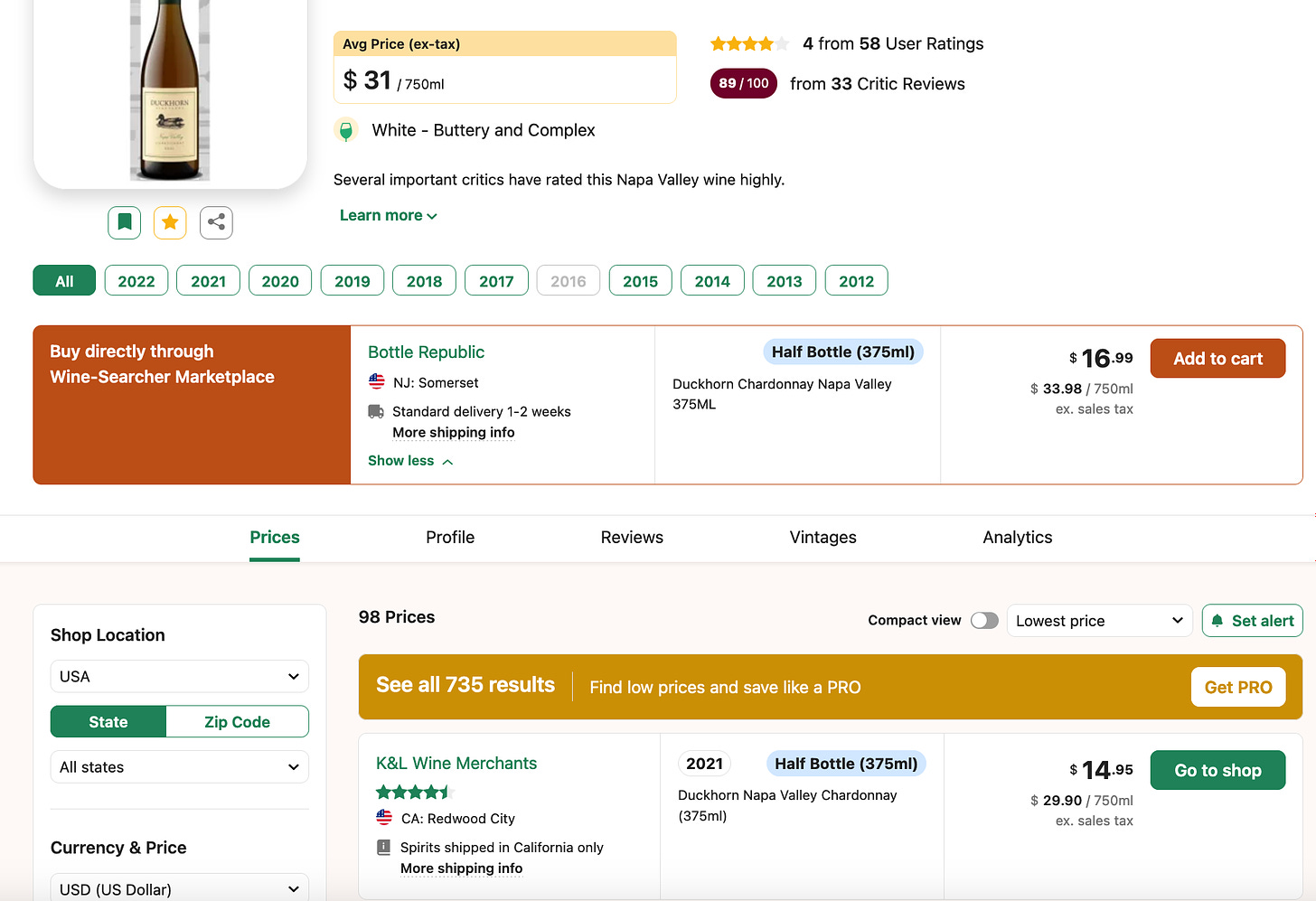

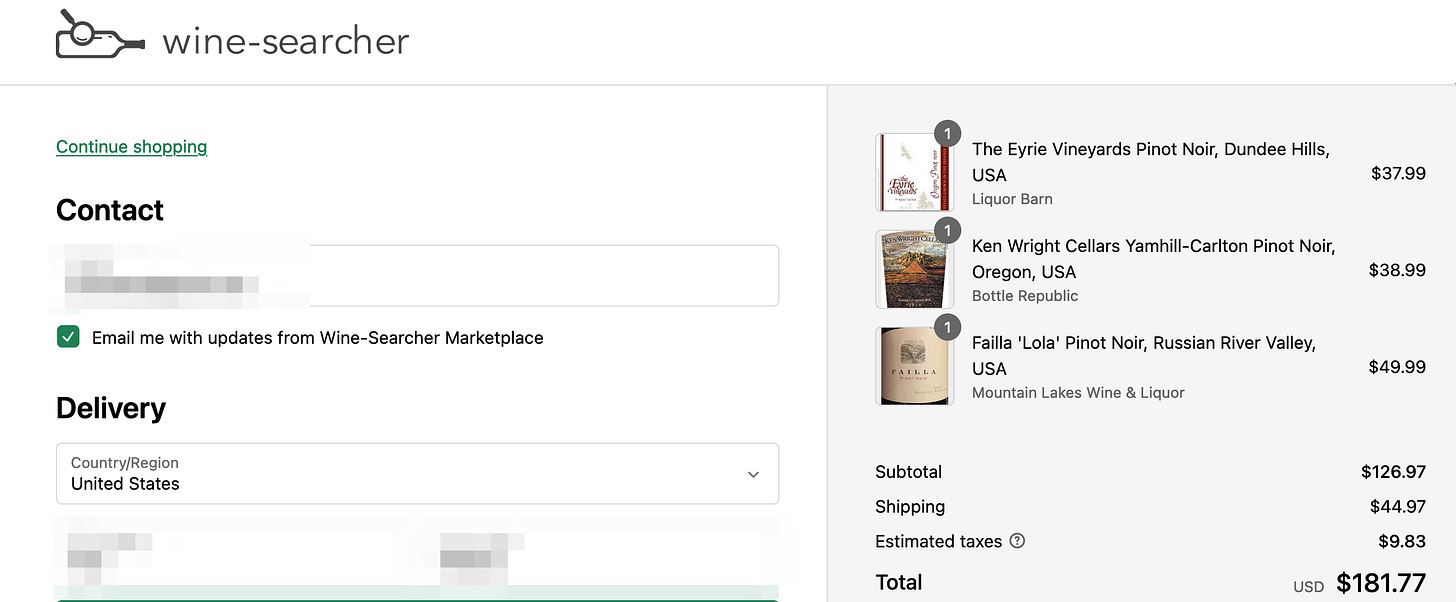

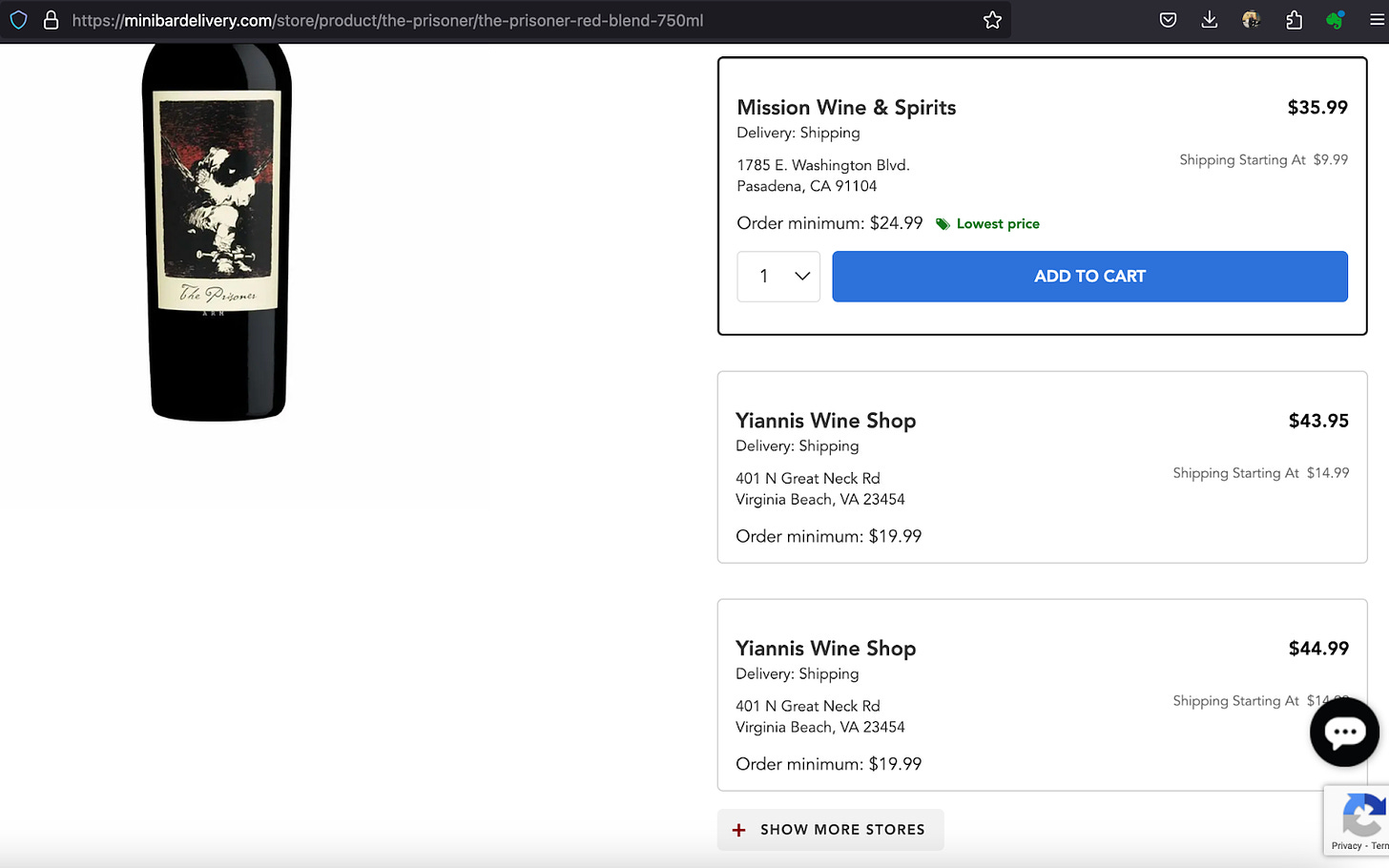

On WineSearcher's new marketplace, retailers pass the shipping rate along to the consumer. It costs nearly $45 to ship three bottles of wine. Talk about a way to quickly dissuade a consumer from making a sale . . .

Shipping is a problem that ALL marketplaces must overcome.

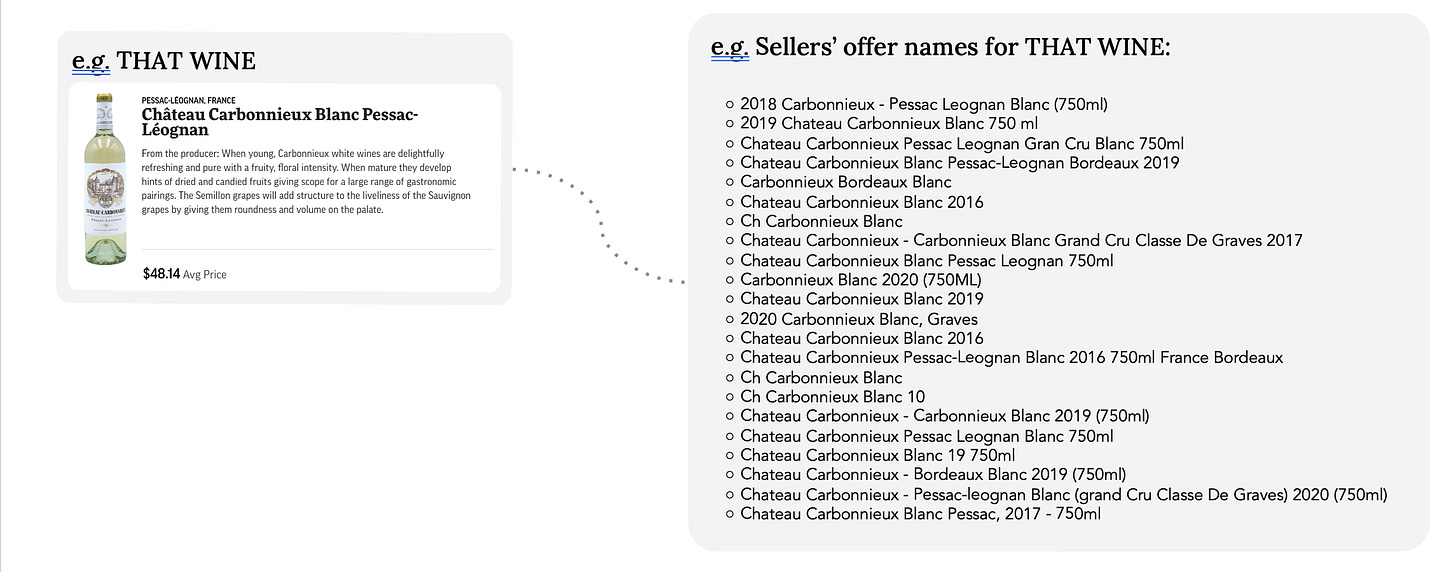

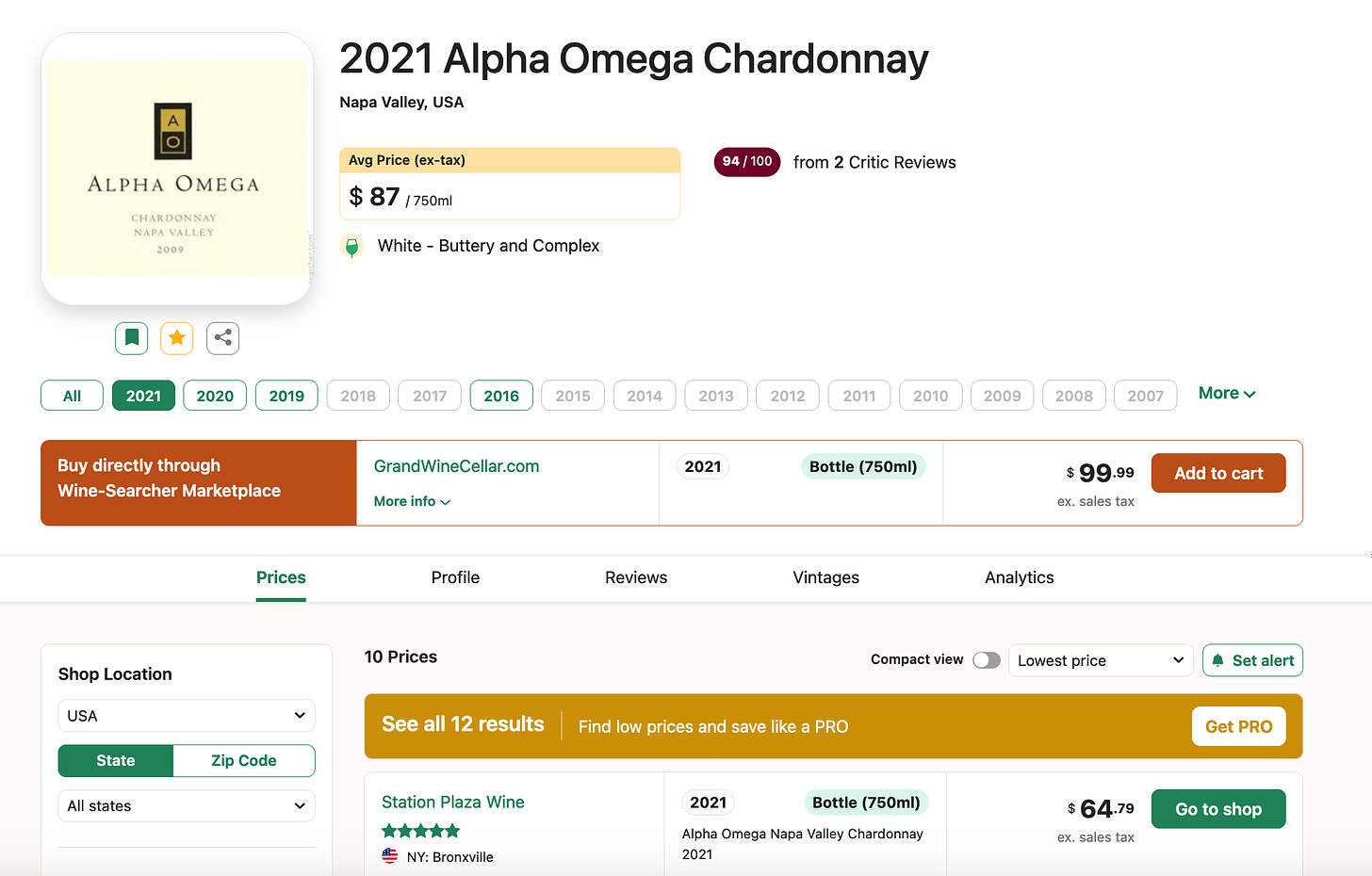

Beyond shipping, marketplaces face tremendous operational challenges, starting with the complexity of products, such as proper wine matching, the geographic availability of the same products across multiple markets, limited retailer margins, consolidating inventory, and state registration for products shipping into a state. These create a complex web that is incredibly challenging to operationalize and maintain.

When you add that marketplaces have the same growth ceilings as etailers, it makes it hard to see how one can possibly succeed and why there is a graveyard of failure in this segment of wine and spirits.

However, every VC wants a marketplace, and many entrepreneurs continually see it as a viable model. Marketplaces are in vogue because, if built right, marketplaces eat markets. What does this mean?

THE INSIDIOUS NATURE OF MARKETPLACES

A marketplace is a kleptoparasite. This means that it steals the income and customers from businesses and makes them its own. But marketplaces are devious about how they have masked their intent. They promise an increase in sales, but essentially, they borrow a seller's inventory, capturing the margin for their services but, most wily, keeping the customer. Without the host, the sellers, and their inventory, they could not exist to steal customers for their own.

That's why when wineries or spirits companies point to marketplaces that keep the customer as their own, they are essentially surrendering that customer to the platform to realize the lifetime value of that buyer but also sell other products. Marketplaces almost always mature to manufacture their products. This has always been true. If you think of major mega-retailers (Costco, Target, Walmart, Safeway) as early analog versions of marketplaces, the built private label brands that dominate their shelves (Kirkland, Favorite Day + 44 other brands, Great Value +, Signature Select +, respectively). But unlike brick-and-mortar retailers. In that case, this has been especially controversial with web-based marketplaces that leverage data to create brands but also to put those brands at the top of search results.

There are also countless examples of other ways marketplaces game the system to the detriment of the market in which they participate -

Doordash - Funneling sales away from non-participating restaurants.

Doordash - Charging exorbitant and miscalculated fees to a restaurant.

Expedia - Dominating SEO and preventing a small hotel from getting reservations.

This is why a WineSearcher marketplace is not a good value proposition. When weighing the value of products sponsored for small ad earnings versus those participating in their marketplace at more significant margins, the new owners will always opt for the latter. I know many retailers watching their traffic closely since the release of the new marketplace and evaluating the ROI of continuing to advertise or look for other solutions.

Retailers and wineries who lend their inventory to marketplaces are building a kleptoparasite, not their partner. And it’s not like we don’t have endless warnings from other industries.

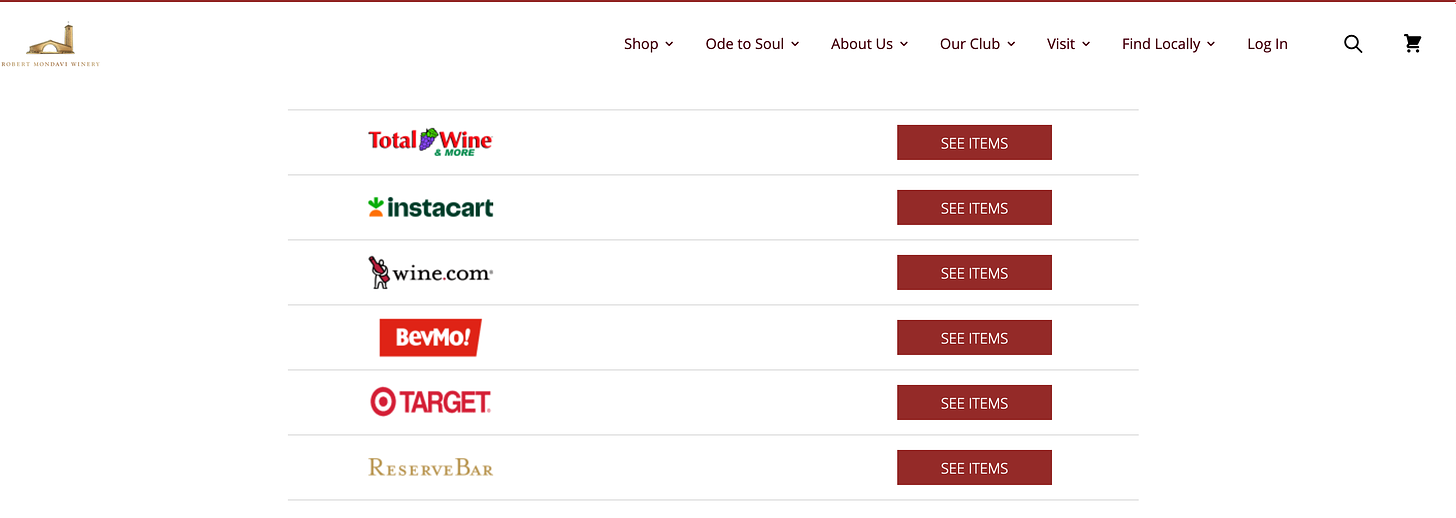

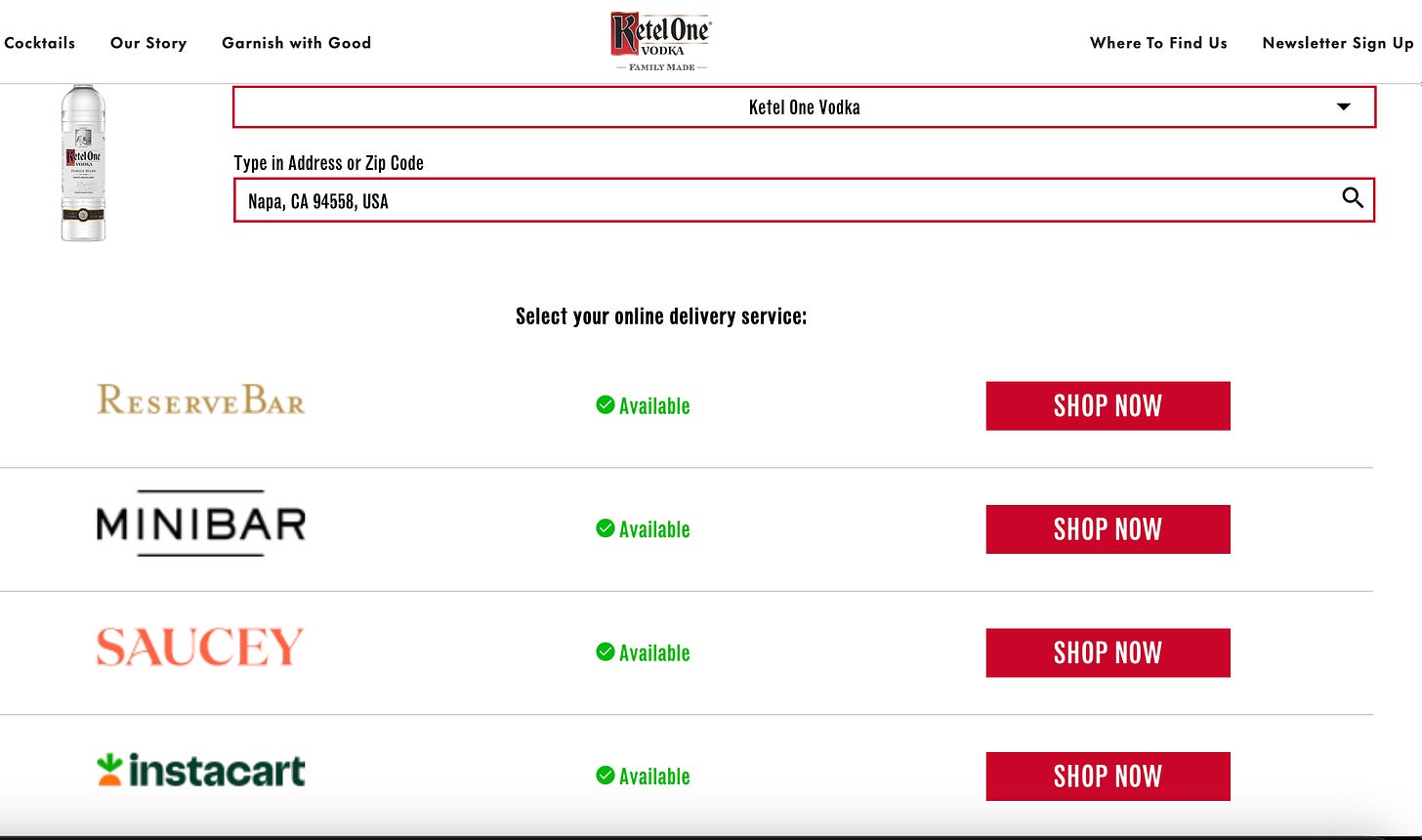

This is made worse when sellers not only lend their inventory but also send consumers to these marketplaces -

Due to their inability to get the customer and realize the LTV (Lifetime value), very few specialized or credible retailers (Total Wine, K&L, Gary's, Wine Library, Zachy's, Wine.com) participate in these models unless they have giant users bases and the potential loss of sales is too high. However, when they do participate, marketplace sales generate the least value for the operations, both in terms of sustainability and profitability.

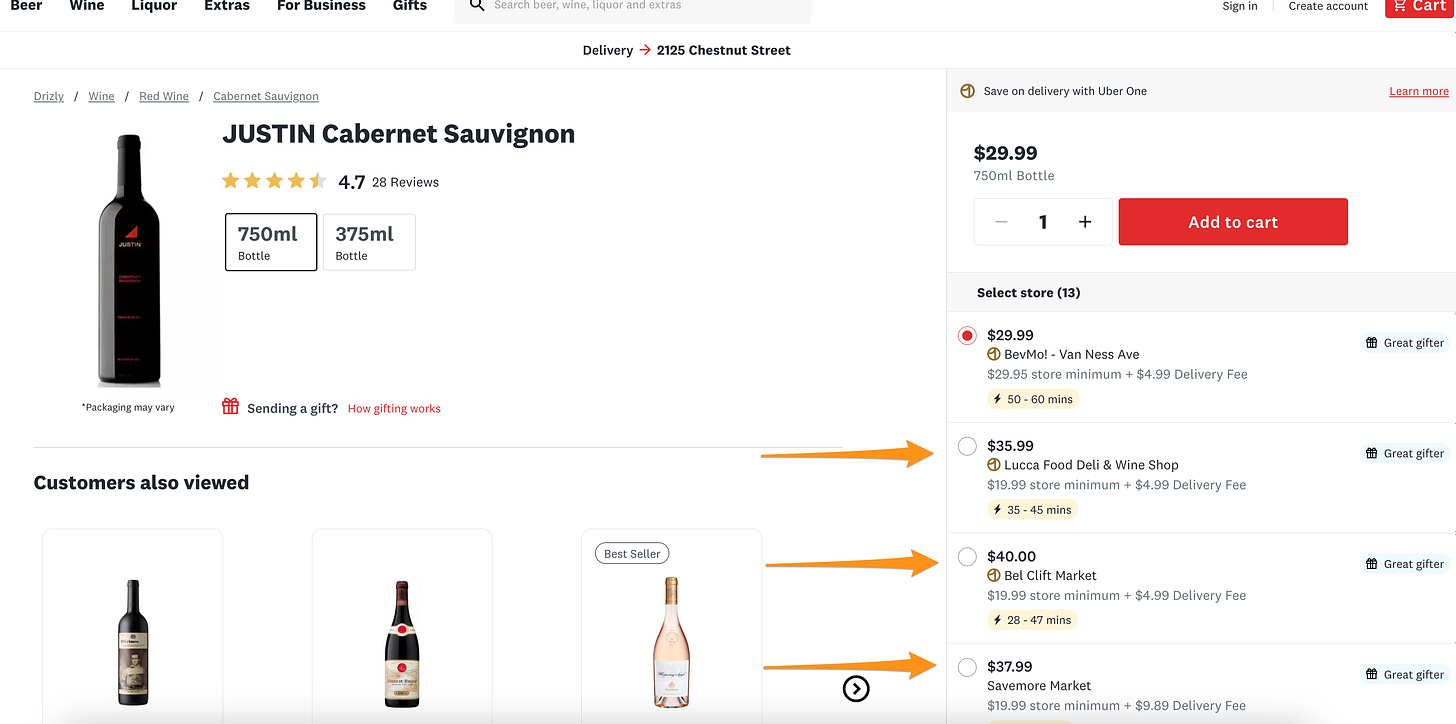

However, marketplaces create value for retailers where the customer LTV has no value, just the incremental revenue for the seller. These are generally stores with an alcohol seller's license that have poor locations, anemic foot traffic, or their business model doesn't consider reselling to a customer on the web. Generally, these are convenience stores, smaller supermarkets, or liquor stores. Their value is any incremental revenue that the marketplace sends their way, and those marginal dollars help subsidize employees or other operational costs not supported by their current business. We often call these "Dark" or "Ghost" retailers, and like Dark Kitchens, they were born from COVID-19. Unfortunately, the reward structure for marketplaces is that the retailer with the lowest price earns the top spot. The results are that these Dark Retailers, who only want to earn incremental sales, race to the lowest price.

This has significant brand consequences while also "lowering the lake" for non-participating retailers. There is even a trend of specialized niche retailers looking to evolve beyond the Dark Retailer model into Alc-Bev “Dark Warehouses” whose primary business is powering multiple marketplaces.

Since we are late to the marketplace game, we can be smarter by learning from other industry’s mistakes under the yoke of marketplaces (read this article from Eater about restaurant delivery services). We should speak with other industry leaders to better understand the positive and negative consequences of marketplaces. My friend and colleague, Nabeel Alamgir, has been leading the fight to liberate restaurants from the yoke of marketplaces and is not only an innovator in how he builds technology to solve this problem but also a vocal protagonist about the negative consequences they bring to an industry. We need to bring these types of voices to our industry and listen to their perspectives before a major marketplace takes root. Wine sellers need to understand how lending their inventory benefits the marketplace as much, if not more, than them.

But this especially includes how wine brands understand how participating and advertising with these platforms not only negatively affects their partners but also has negative consequences for their brands beyond the immediate gratification of some quick sales. This is most important now when the need to sell wine is so acute, but our decisions could create a monster of our own that will consume us in the future. Marketplaces eat markets.

Wow - that was nearly a book. I promise a much shorter piece next. Inspired by

‘s amazing article, “Nothing Left to Say? The End of Wine Writing,” I want to followup with a deep dive into the challenges of online wine content.

hey paul - great post, would love to chat with you about the topic and will reach out on linked in.

Yes...yes....to all of this!