The E-tailer Glass Ceiling

All the reasons why it is highly unlikely that we'll ever have an Amazon for wine.

Ever wonder why there is no Amazon for wine? Why no wine e-tailer can service all the wines you could ever want to buy? The answer may surprise you.

Wine is an infrequent purchase from various retailers, different brands, and multiple purchasing modalities, i.e., people always buy wine differently based on location, needs, and availability. One day, you may buy groceries and add wine to your cart from what is available. The next, you are out to dinner with your friends and choose from what is on the list. Another day, a special guest comes to your house, so you go to the boutique wine shop. Finally, if you are looking for something special at a discount or delivered quickly, you might go online to buy it. This makes a wine consumer an elusive frequent customer: wine is so readily available and interchangeable that brand and retailer loyalty is a rarity. And this underlies some of the core challenges with e-tailing.

The actual time a consumer consumes a wine after purchase is clouded in endless wine lore; the theoretical estimated times vary from four hours to one week. However, the consensus of most researchers is that over half of the people buying wine intend to drink it within 48 hours of purchase. This provides significant headwinds for an online retailer to change consumer behavior, such as the patience to buy wine online, which requires overcoming shipping time and costs. Now, you may say that this is the problem with any e-tailer delivering a product, and to some degree, you'd be correct. However, most products aren't shipped in fragile glass containers, with ingredients that are susceptible to heat and cold and require an adult signature to be delivered. Still, wine has even more unique challenges that create incredible friction and a glass ceiling for how big a wine e-tailer can become.

What would seem simple and the most basic of functions for any online seller, sourcing, and buying products, are not easy tasks for wine sites. It's crazy how complex the process is to stock an online wine store. Buying 19 Crimes, Bota Box, Kendall Jackson, Louis Jadot, Kim Crawford, Penfolds, Duckhorn, Rombauer, and many mainstream brands is relatively easy. But buying small-production wine is incredibly challenging. This is because the long-tail wines are for sale through a patchwork of small wholesalers. While SevenFifty (now owned by Provi) makes it easier to find who sells wine, a retailer must create accounts with many different wholesalers and importers to buy the wine. While this is merely a headache, the more significant problem is that they can ONLY buy wines from "the primary source wholesaler" (the only wholesaler legally designated and allowed to sell that wine in the state).

The intent was to prevent counterfeit products, but the actual outcome has only narrowed the ability to find alternative sources to purchase wines from alternative wholesalers. This both narrows selection and stifles market access for wines. Outside of their local state, retailers are also prohibited from buying directly from producers/importers without going through state wholesalers. This also limits market access for both brands AND products. A wholesaler may only want to carry one product but not the rest of a winery's portfolio. That means that if wine products are unavailable in a retailer's state from a wholesaler, it's impossible to sell them on the site or have to build a complex licensing network across multiple states to attempt to create a better sourcing footprint. It also means that the cost of those wines has a 25%-35% margin loss for the retailer or passed on to the consumer, inflating the final price. This is one reason Wine.com will NEVER become the Amazon of wine.

And, even if a retailer builds a multi-state licensing infrastructure, their inability to use a central warehouse and share inventory across those licenses is illegal, forcing them to duplicate inventory in multiple states. And because retailers are not allowed to have wine on "consignment," the carry costs for inventory, especially as you try to fulfill the smaller, more expensive, long tail producers, limit how the selection wine they can stock and thus sell. Outside of wine and other e-tailer categories, they succeed by stocking inventory without paying until the sale occurs, or they present the manufacturers' inventory to sell and drop ship (e.g., Wayfair, Amazon, Apple, and more.

Assuming a retailer is the David Blaine of selling wine online and overcomes the challenges of building an attractive online wine store, they still face an invisible challenge: the monumental feat of merchandising the wines on the site. Wine is a complex product with lots and lots of supporting data. There are over SEVENTY metafields of data for every single product. Everything from the name, the region, the variety, and the price to more nuanced elements like elevage, soil, winemaker, vineyard practices, grape clones, seasonal weather notes, and more. So many more. There are tools for document asset management that help overcome these challenges. Still, outside a few of the largest wine companies like Constellation, Treasury, Gallo, etc., few wineries use product information management (PIM) tools like Salsify or Syndigo to deliver the correct and current product data to seed retailer's sites. And even if they do, the way they use data in these tools has no standardization, and outside of the largest retailers, very few have the technical capacity to consume those data feeds or desire to integrate with dozens of different suppliers.

Additionally, most companies that create data feeds are only concerned with current releases rather than data from older vintages. They also tend only to provide the very minimal fields to support the wine to be listed for sale: size, price, variety, name, region, etc. Not the full spectrum of meta-data that a luxury wine retailer might be interested in sharing with their consumers.

Here is a typical example of minimal product information retailers share with consumers. As you can see, it's not very helpful for consumers to make purchasing decisions.

But the challenge grows exponentially as you get into the long-tail wines and the changes in wine information thanks to the ever-changing vintage variations thanks to Mother Nature. Because there is no universal database for wine, there is no central repository for getting accurate information. The few sites with an extensive enough data set to power a universal wine database have built walled gardens and feel that data is their competitive advantage. Getting the data directly from the producers poses equally problematic challenges. Winery sites are notorious for making it hard to find the data. From wine data (often differing data) in the shop and the trade section or downloadable PDFs, barriers to wine information because the product is allocated like this winery or this winery. Or equally problematic, readily having information on past vintages still for sale in the market or possibly in consumers' cellars. Even big brands like Mondavi or Cakebread suffer from allowing past vintages to vanish in time. Compare this to the excellent representations of Silver Oak, Opus One, or Peter Michael. And let's not even get started on the wineries that don't have websites at all - here's a small example of one region with over half of the producers without websites.

Let's imagine a retailer rotating through 2K-80K products annually and paying $16 per product to collect, enhance, and publish a wine product on the site. The cost of just managing wine products means that retailers could be spending up to $38K - $1.3M, respectively. Even assuming the cost of the upper range is half or a quarter of that amount, the total effort to properly merchandise the store for a wine e-tailer is an incredible financial and resource burden.

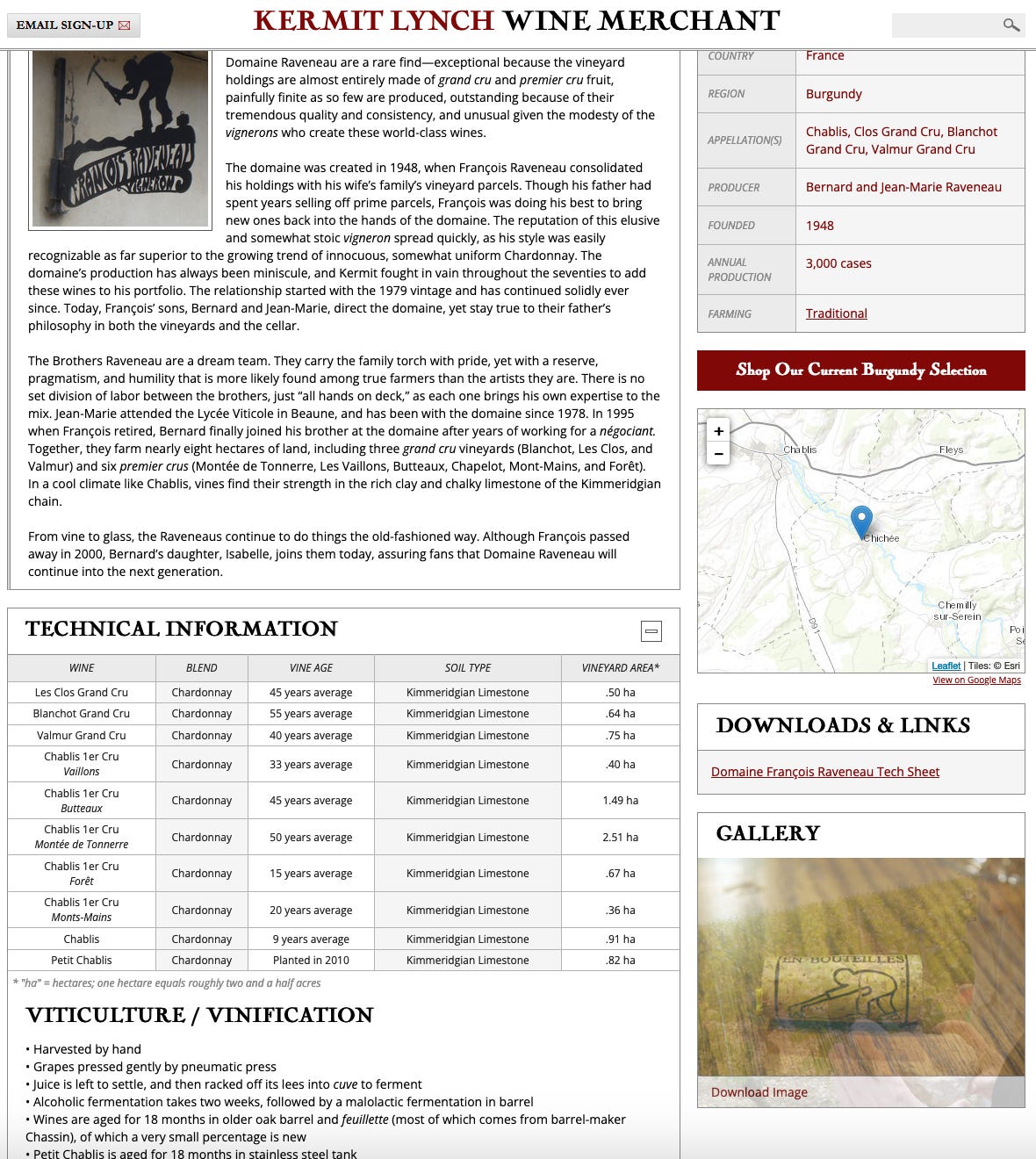

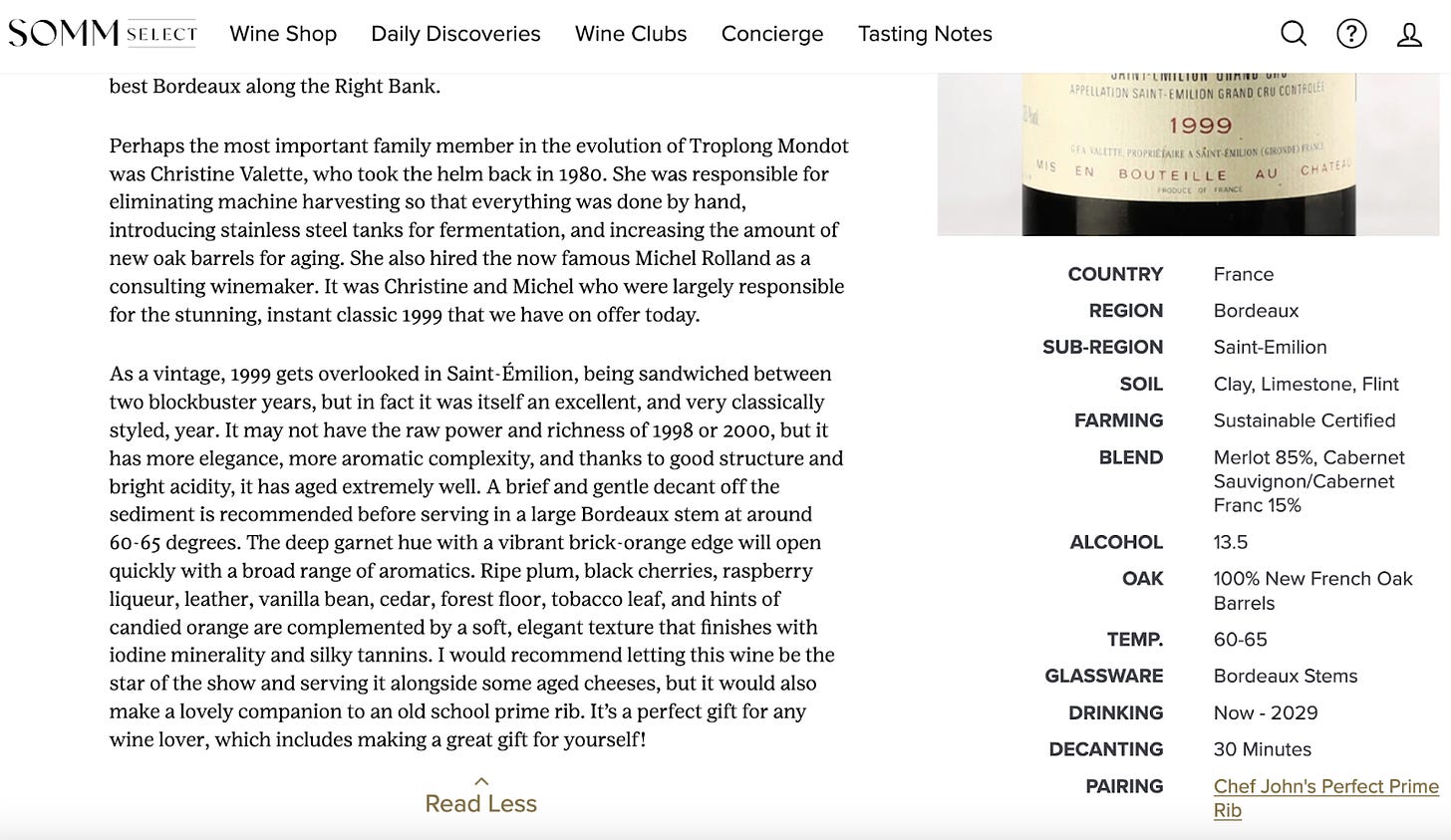

Look at how richer the two experiences below are for a consumer when there is better information about the wine -

Contrast this against an incredibly expensive wine with no context or information, and what a disservice it is for someone trying to buy this bottle of Colgin.

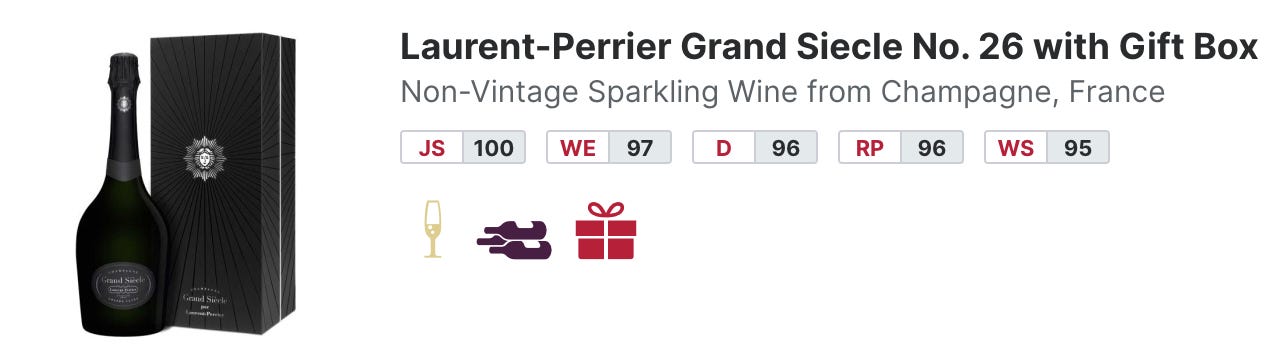

Let's not forget the need/desire to overlay professional critics' reviews only content and operational costs for the retailer. Make no mistake, I believe that critics should be compensated for their work. Still, the current content partnership models are operationally and economically challenging for retailers to both match those reviews to products (or off-load those efforts to the critics) and only review a portion of the wines they sell with a subset of critics or pay for all critics and duplicate costs for many products buy licensing all the critics. As such, many retailers skirted critics' royalties by only entering their initials and scores.

Examples of retailers circumventing paying by only using initials and scores.

However, after passing through both the buying and merchandising gauntlet of setting up an online store, one can not ignore the regulatory weight that lies heavy on the shoulders of a retailer. In 2005, the wine industry had a landmark case to make it easier to sell wine online. Granholm was a game-changing case that unlocked the dormant commerce clause - if you allow intrastate commerce activities, you need to enable interstate commerce activities. This unlocked interstate sales for wineries, but somehow, retailers were excluded from this pivotal decision. As such, retailers can only ship to fourteen states and, like wineries, are restricted to volume purchasing limits (per household or person). These regulations limit how much a retailer can sell a customer in a period, regardless of the buyer's desire or capacity. The National Wine Retailers Association (NWRA) works tirelessly to unburden wine retailers' limitations and antiquated regulatory challenges. Despite resistance from opposing constituents, their success in implementing change is inevitable. Wineries have already paved the roadmap. They have, without any certainty, proven that interstate shipping does not induce underage drinking and allows for effective tax collection. However, when the inevitable shipping changes occur, the buying and selling power dynamics will favor retailers on the coasts or with large multistate footprints. i.e., even with shipping, retailers on the West Coast can buy and sell CA, OR, and WA (and others) wines cheaper than East Coast retailers, while the opposite will be valid for NY and European Wines.

Acquiring online wine customers is expensive. The customer acquisition cost (CAC) is estimated at approximately $168 per customer for qualified wine consumers. Extracting a meaningful lifetime value from that CAC is incredibly challenging due to their infrequent online purchasing behavior.

Now, assuming an e-tailer successfully overcomes ALL of these factors, the fundamental limiter that creates the ceiling for growth is more significant than these four factors together. The limitations to becoming the Amazon of wine online are in the product's DNA.

The advantage of online retailers usually lies in the diversity of their product offerings. As mentioned, scaling wine sales is often constrained by limited production. Nothing illustrates this more than a conversation I had with a significant online retailer after the end of the pandemic. They said they were down in sales. I empathized with them about it being an industry-wide problem, but they immediately disagreed. "We could keep doubling our sales, but now that the world has returned to normal, the wines that our customers love are being reallocated to restaurants and brick-and-mortar retailers. Before, we were getting 250-3000 cases of amazing brands, but now we are lucky if we get a few pallets. It's hard to make your numbers when you're limited in what you have to sell." So, the limitations of how brands, with consumer demand, allocate their wines to online retailers are the critical limiters of their success. The alternative is for these retailers to carry large-production wines. Since those wines are easy to find in the market, it essentially forces the online retailer to compete with local retailers on price, convenience, and immediacy (two of the three are always a losing proposition for the e-tailer). That means that for an online retailer to be successful, they need significantly larger quantities of boutique or high-priced wines, which, by nature, have a limit on how much they can allocate to the retailer or even make and, even if they were magically able to grow, they are no longer boutique or unique. This is very different than most other online products. When most other products, even long-tail products, succeed, they make more. That is an impossibility with wine. And that is why the constrictions of wine production become the limiting factor for an e-tailer.

When you add all of these up, they combine to become a multifaceted puzzle that has stymied online wine retailers like Wine.com, Winlibrary, and more to never exceed $500M in annual sales. In comparison, a retailer like Total Wine, which is "clicks and mortar," can sell across the spectrum, fulfill the consumer's needs across all channels, and solve many regulatory barriers by having a large geographic footprint to conform to state regulations and overcome volume limitations. It's the ability to serve a customer across multiple buying occasions, across various channels, a large selection across price points and brands, with a sprinkle of products only available at their stores, are the essential ingredients that make Total Wine successful and can not be replicated by a pure-play online retailer.

Are there unconventional wine-selling models that can break the glass ceiling? Let’s explore Flash Sales sites next . . .

That about sums it up Paul!

Sorry for all the errors in today’s post. I was rushing to publish it, and in my late-night push, I didn’t update the article with my final edits.